2306

Disrupted Brain Network Topology in Pediatric Tourette Syndrome: A Resting-State fMRI Study1Department of Radiology, West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, People's Republic of China

Synopsis

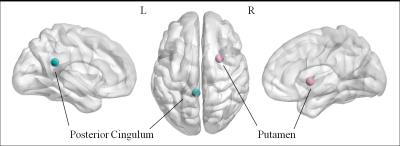

Tourette syndrome is a neurobehavioral disorder characterized by motor and vocal tics beginning in childhood. Previous neuroimaging investigations suggested impaired cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical activity during motor control. We hypothesized that the small-world properties of functional connectomes would be abnormal in pediatric Tourette Syndrome patients. Compared with control subjects, the Tourette Syndrome patients showed altered quantitative values in the global properties, characterized by higher path length, higher normalized characteristic path length and lower global efficiency, implying a shift toward regular networks. The Tourette Syndrome group showed decreased nodal efficiency in the posterior part of left cingulum and right putamen comparing to the controls.

Introduction

Tourette syndrome (TS) is a neurobehavioral disorder characterized by motor and vocal tics beginning in childhood.1,2 Tics are involuntary, repetitive muscle contractions that produce stereotyped movements (motor tics) or sounds (vocal tics). Previous neuroimaging investigations suggested impaired cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical activity during motor control.3 However, the topological characteristics of the functional connectomes in pediatric Tourette Syndrome patients are largely unknown. Based on the abnormal cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical curcuit, we hypothesized that the small-world properties of functional connectomes would be abnormal in pediatric Tourette Syndrome patients.Methods

Twenty-five patients with TS and 22 control subjects were

included in the study after quality check of the data. The groups were matched

for age, gender, education year, handness. For patients, inclusion criteria

were aged under 18 years and confirmed DSM-IV-TR criteria for TS. The severity

of tics symptoms was assessed using the Yale Global Tics Severity Scale

(YGTSS). Exclusion criteria were (i) co-occurring psychopathology (current

depression, epilepsy, current or previous history of psychosis); (ii)

developmental retardation, cerebral palsy, small for gestational age,

history of asphyxia at birth, history of cord around neck; and (iii) contraindications

to MRI examination. Control subjects’ inclusion criteria were: aged under 18

years and no history of neurological or psychiatric disorders. The exclusion

criteria were the same as for patients. Also previous history of tics

(childhood tics) and any type of medication were excluded.

Each subjects in both groups was assessed using the

Stroop Test, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), Child Behavior Checklist,

general neuropsychological assessment including character memory, graphics

memory, verbal influence, scarification test.

A rest-fMRI dataset was acquired using a 1.5T magnetic

resonance system (Philips Archieva Nova dual)

with an eight-channel phased array head coil. The participants were instructed

to keep their eyes closed and to think of nothing in particular during the

acquisition. Head motion was minimized with foam pads. The sequence parameters of the blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD)

signal were repetition time/echo time (TR/TE) 3000/50 ms; flip

angle 90°; 30 axial slices

per volume; 4 mm slice thickness (no slice gap); matrix 64×64; field of view (FOV) 230×230 mm2; voxel size 3.59×3.59×4.00 mm3. A total of 150 volumes were

collected for each subject. All of the MR images were evaluated for clinical

abnormalities by a neuroradiologist (Haibo Qu, 10 years of experience). Image

preprocessing was performed using SPM8 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). The

first 10 time points were discarded to avoid instability of the initial MRI

signal.

Functional

connectivity between 90 brain regions from the automated anatomical labeling

atlas was established using partial correlation coefficients, and the

whole-brain functional connectome was constructed by applying a threshold to

the resultant 90×90 partial correlation matrix. Graph theory analysis was

then used to examine the group-specific topological properties (e.g.,

small-world, efficiency, and nodal centrality) of the two functional

connectomes. The network was constructed using GRETNA (http://www.nitrc.org/projects/gretna/)Results

Twenty-five TS patients (mean age 8.48 ± 1.98 yr) and 22 healthy controls (mean age 8.36 ± 2.04 yr) were participated in this study. The demographic and clinical characteristics of these groups are summarized in Table 1. All TS patients' scores of YGTSS and disease duration were presented in Table 2. All participants were right-handed. The Tourette Syndrome group, compared with the control group, showed a significantly decreased global efficiency(P=0.0141), increased path(P=0.0082) length and normalized characteristic path length(P=0.0357) ( false discovery rate corrected). Compared with the control group, the Tourette Syndrome group showed decreased nodal efficiency in the posterior part of left cingulum(P=0.0001) and right putamen(P=0.0003)( false discovery rate corrected).Discussion

Compared with control subjects, the Tourette Syndrome patients showed altered quantitative values in the global properties, characterized by higher path length, higher normalized characteristic path length and lower global efficiency, implying a shift toward regular networks. The nodal efficiency was decreased in the right putamen, involving in the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical curcuit. These findings accord with the finding that chemical or electrical stimulation of inputs into the putamen can provoke motor and phonic responses that resemble tics.4 The results provided unequivocal evidence of a topological alteration of the functional connectome in pediatric Tourette Syndrome.Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81601460) , Health and Family Planning Commission of Sichuan Province Scientific Research Program (Grant No.16PJ245) and Sichuan Scientific Innovation Seeding Program (Grant No. 2016051).References

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders;1994.

2. Leckman J, Cohen D. Tourette’s Syndrome – Tics, Obsessions, Compulsions: Developmental Psychopathology and Clinical Care. John Wiley & Sons.1999.

3. Roger L. Albin, Jonathan W. Mink. Recent advances in Tourette syndrome research. TRENDS in Neurosciences. 2006;29 (3) :175-182.

4. James F Leckman.Tourette’s syndrome. The Lancet, 2002;360(9345):1577-1586.

Figures