2280

Prenatal Maternal Depression and Anxiety Alter Hippocampal Development in Fetuses1The Developing Brain Research Laboratory, Children’s National Health System, Washington, DC, United States

Synopsis

The hippocampus plays an important role in stress regulation. This study aims to investigate the relationship between prenatal maternal stress and fetal hippocampal volumetric growth using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Results suggest that maternal depression and anxiety are associated with smaller left hippocampal volumes in female fetuses in the third trimester of pregnancy.

Purpose

Abnormal hippocampal development is associated with a range of neuropsychiatric disorders. Clinical MRI studies in adults diagnosed with major depressive disorders have reported reduced hippocampal volumes,1,2 while adults at risk for anxiety and depression have reduced volume in the left posterior hippocampal region.3 Recent studies have shown that prenatal maternal stress is associated with larger amygdala in their offspring at school age,4,5 but no differences in hippocampal volume. Conversely, infant studies report that increased prenatal maternal anxiety is associated with smaller hippocampus over the first 6 months of life.6 Moreover, available animal models suggest that prenatal stress leads to disturbances in the development of the hippocampus in their offspring.7,8 These findings raise the intriguing question of whether prenatal maternal stress may adversely affect the development of the hippocampus in human fetuses in vivo. Therefore, we sought to examine the association between prenatal maternal stress and hippocampal volumetric growth in healthy fetuses using MRI.Methods

In the context of a longitudinal prospective study, we recruited healthy pregnant women from low-risk obstetric clinics and with normal ultrasound and fetal biometry studies. We excluded women with physical (e.g., metal implants) or psychosocial (e.g., claustrophobia) contraindications for MRI, as well as MRI scans with poor image quality. MRI scans were acquired in axial, coronal and sagittal planes using 1.5T GE DISCOVERY MR450 (single shot fast spine echo; repetition time: 1100 ms; echo time: 160 ms; flip angle: 90º), and were reconstructed into a single high resolution 3D volume using Baby Brain Toolkit. The reconstructed images had a voxel size of 0.8594×0.8594×0.8594 mm3. The left and right hippocampi were manually delineated on 3D reconstructed T2-weighted MRI scans by using ITK-Snap software. All hippocampi were manually segmented twice by the same rater following a previously validated protocol.9 Results from the second manual delineation were used in the statistical analysis. Intraclass correlation coefficients for repeat delineations were 95.83% and 96.05% for left and right hippocampi, respectively. Three maternal questionnaires assessing anxiety and depression: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), Speilberger State Trait Anxiety Inventory-State (STAI-S), and Speilberger State Trait Anxiety Inventory-Trait (STAI-T) were completed by the pregnant participants on the same day of the fetal MRI scanning. Male and female fetuses were classified into two subgroups and analyzed separately. Multivariate regression analyses were used to examine associations between fetal hippocampal volumes (i.e., left and right) and each of the prenatal depression/anxiety measures (i.e., EPDS, STAI-S, and STAI-T). Correlations between plausible independent (i.e., gestational age (GA) at MRI, maternal education, paternal education, maternal employment, paternal employment, and maternal race) and dependent variables (i.e., left and right hippocampal volumes) were examined. Final analyses included prenatal depression/anxiety scores and GA at MRI as independent variables for all multivariate regression analyses.Results

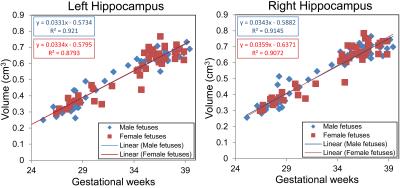

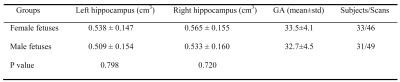

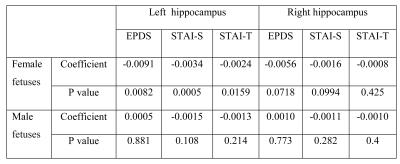

We performed 95 MRI studies on 64 healthy fetuses (31 males, 33 females) between 25-40 weeks of gestation (mean±SD=33±4.3 weeks), of which 31 pregnant women underwent two fetal MRI studies at different GAs. All fetal brain MRI studies were reviewed by an experienced fetal neuroradiologist and were found to be structurally normal. Left and right fetal hippocampal volumes increased linearly with advancing GA in both males (left hippocampus: r=0.0331, p<.0001; right hippocampus: r=0.0343, p<.0001) and females (left hippocampus: r=0.0334, p<.0001; right hippocampus: r=0.0359, p<.0001), as shown in Figure 1. Means and standard deviations of left and right hippocampal volumes in male and female fetuses are shown in Table 1. The hippocampal volumes in male and female fetuses were not significantly different (left: p=0.798; right: p=0.720) after controlling for GA. The regression results of each maternal stress measure and fetal hippocampal volumes are shown in Table 2. Interestingly, increased maternal depression and anxiety as measured by EPDS, STAI-S, and STAI-T were associated with smaller left hippocampus in female fetuses (EPDS: r=-0.0091, p=0.0082; STAI-S: r=-0.0034, p=0.0005; STAI-T: r=-0.0024, p=0.0159), but not in male fetuses.Discussion and Conclusion

We report for the first time that prenatal maternal depression and anxiety are associated with reduced left hippocampal growth in female fetuses only. These intriguing data suggest that prenatal maternal depression and anxiety preferentially affect females in the third trimester of gestation suggesting a potential critical period of hippocampal development in females, but not males. Ongoing work is needed and currently underway to examine the impact of prenatal maternal stress on long-term social-behavioral outcomes.Acknowledgements

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health-R01 HL116585-01.References

1. Huang Y, Coupland NJ, Lebel RM, et al. Structural changes in hippocampal subfields in major depressive disorder: A High-Field Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74:62–68.

2. Maller JJ, Daskalakis ZJ, Thomson RH, et al. Hippocampal volumetrics in treatment-resistant depression and schizophrenia: The Devil’s in De-Tail. Hippocampus. 2012;22:9–16.

3. De Geus EJ, Van't Ent D, Wolfensberger SP, et al. Intrapair differences in hippocampal volume in monozygotic twins discordant for the risk for anxiety and depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(9):1062-1071.

4. Buss C, Davis EP, Shahbaba B, et al. Maternal cortisol over the course of pregnancy and subsequent child amygdala and hippocampus volumes and affective problems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012;109(20):E1312-E1319.

5. Lupien SJ, Parent S, Evans AC, et al. Larger amygdala but no change in hippocampal volume in 10-year-old children exposed to maternal depressive symptomatology since birth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011;108(34):14324–14329.

6. Qiu A, Rifkin-Graboi A, Chen H, et al. Maternal anxiety and infants’ hippocampal development: timing matters. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3:e306.

7. Glombik K, Stachowicz A, Slusarczyk J, et al. Maternal stress predicts altered biogenesis and the profile of mitochondrial proteins in the frontal cortex and hippocampus of adults offspring rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;60:151-62.

8. Behan AT, van den Hove DL, Mueller L, et al. Evidence of female-specific glial deficits in the hippocampus in a mouse model of prenatal stress. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21:71–79.

9. Ge X, Shi Y, Li J, et al. Development of the human fetal hippocampal formation during early second trimester. Neuroimage. 2015;119:33-43.

Figures