0772

Signal-model-based water-fat separation in Zero Echo Time (ZTE) MRI1University and ETH Zurich, Zürich, Switzerland, 2ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Synopsis

The separation of water and fat in zero echo time (ZTE) imaging is challenging for several reasons: First, echo-based signal models are violated for fast-relaxing spins and require the use of loud sequences. Second, frequency selective preparation pulses produce large SAR and are inefficient on short-T2 compounds. Finally the off-resonance induced phase vanishes at TE = 0. In this work, we introduce the principles of a technique that allows water-fat separation for a single ZTE acquisition and demonstrate it potential and limits with phantom and in-vitro experiments.

Purpose

Zero Echo Time (ZTE) MRI1 is used for imaging short-T2 compounds and has furthermore the advantage of producing only low acoustic noise. Separation of water and fat in ZTE images is challenging because: 1) Echo-based signal models as described in Dixon2 or Ideal3 are violated for fast-relaxing spins and require the use of loud sequences. 2) Frequency selective preparation pulses produce large SAR and are inefficient on short-T2 compounds. 3) The off-resonance induced phase vanishes at TE = 0. In this work, we introduce the principles of a technique that allows water-fat separation for a single ZTE acquisition.Theory

Water-fat separation is done by solving an inverse problem. The signal model of a ZTE sequence is written in k-space in a similar fashion to what was described by Levin et al4 in order to account for the dephasing happening during the acquisition duration:

$$$s(\tau_k) = \sum_{m=1}^{M}[\int \int \int \rho_m(r)\cdot e^{i\gamma G\tau_kr}\cdot e^{i\Delta f_m\tau_k} \cdot e^{i\gamma \Delta B_0(r)\tau_k}\cdot e^{i\phi_{coil}(r)} \cdot e^{i\phi_{global}}dr ] = \sum_{m=1}^{M}[\int \int \int \rho_m(r)\cdot enc_m(r,\tau_k)dr]$$$

with $$$s(\tau_k)$$$ the complex k-space signal acquired at time $$$\tau_k$$$, $$$\rho_m(r)$$$ the real-valued proton density of chemical species m, G the encoding gradient, $$$\Delta f_m$$$ the chemical shift of species m, $$$\Delta B_0(r)$$$ the frequency offset due to heterogeneous sample magnetic susceptibility, $$$\phi_{coil}(r)$$$ the coil-induced phase, $$$\phi_{global}$$$ an arbitrary global phase and $$$enc(r,\tau_k)$$$ the encoding matrix assembling all these contributions.

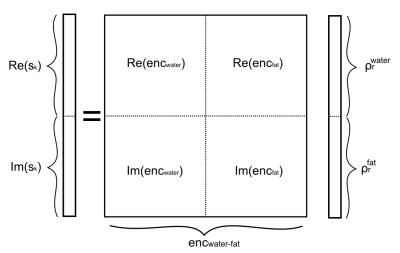

Every k-space point contributes to 2 equations, one real and one imaginary. Thus, for an image matrix of size N, a fully sampled Cartesian k-space leads to 2N equations. Assuming that all phase contributions are known, the additional degree of freedom can be used to determine the spatial location of a second chemical species by rewriting the system in a matrix form as illustrated in Fig 1.

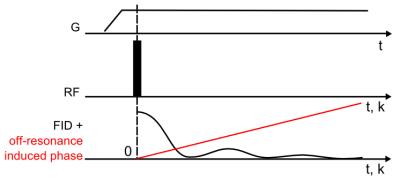

The liability of the inversion of the signal model is described by the conditioning of the encoding matrix which depends on the encoding pattern. In ZTE scanning, the radial center-out acquisitions lead to a linear chemical-shift induced phase (Fig. 2). The small phase difference between water and fat around k0 leads to ill-conditioning of low spatial frequencies, which is, however, compensated by the strong averaging in central k-space, typical for 3D radial acquisitions.5.

Methods

Data was measured using a single ZTE acquisition. Images were reconstructed with an adaptation of the algorithm described by Weiger et al. 1 where 1D projections are obtained by direct algebraic reconstruction of 1D data sets and the final 3D image is retrieved after standard gridding. In this work, the 1D encoding matrix was replaced by that one described in Fig. 1, leading to the reconstruction of two 1D projections (water and fat) per k-space direction. 3D images were then reconstructed from two separated sets of 1D projections.

$$$\Delta B_0(r)$$$ and $$$\phi_{coil}(r)$$$ cannot be accounted for in 1D. Hence, in the present implementation, $$$\Delta B_0(r)$$$ was shimmed with residuals ignored and linear coils were used to avoid contributions of $$$\phi_{coil}(r)$$$. $$$\phi_{global}$$$ was approximated by the phase of the first point of an FID.

Phantom: Glass sphere (inner diameter=5 cm) filled with mineral oil and water. Scanner=7T, no shimming, resolution=1.3 mm isotropic, acquisition duration=500 us, G = 24.5 mT/m.

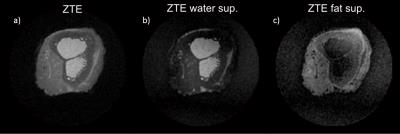

In-vitro: Forefoot joint of a sheep. Scanner=4.7 T, shimmed: fieldmap-based, resolution = 0.5 mm isotropic, acquisition duration=300 us, G = 78 mT/m.

Results

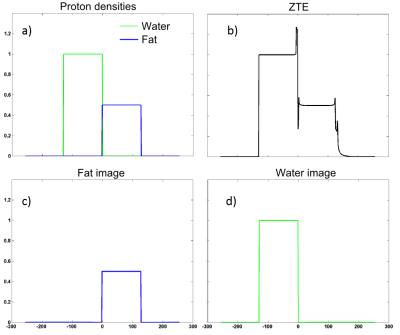

1D simulations (Fig. 3): Application of the proposed algorithm on ZTE data allows the creation of two sharp images when normal reconstruction leads to a single image exhibiting off-resonance artifacts.

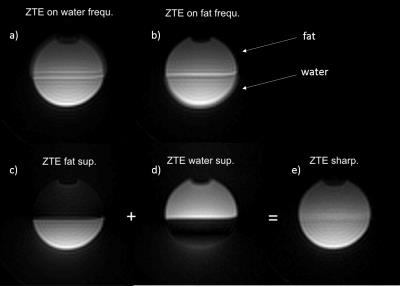

Phantom imaging (Fig. 4): Demonstration that the results of 1D simulations are valid for 3D dataset where the effect of inhomogeneous susceptibility and coil phase are negligible.

Lamb leg imaging (Fig. 5): Water-fat separation is possible in well-shimmed regions but is limited by remaining B0 inhomogeneities.

Discussion

The proposed method has the advantage of being silent, creating low SAR and being suitable for short-T2 imaging. However, its applicability is still limited mainly by B0 inhomogeneities which could be accounted for if they were measured and if reconstruction was performed in 3D, using for example multi-frequency interpolation6 or a CG algorithm7. The proposed approach is compatible with WASPI and PETRA sequences and could furthermore be generalized to multi-frequency fat spectrum in order to improve separation.Conclusion

We set the basis of a k-space based water-fat separation method providing the following advantages: short-T2 sensitive, silent, low power deposition, compatible with ZTE, WASPI or PETRA. We demonstrated its capability using 1D simulations, phantom imaging and in-vitro imaging. Remaining challenges are incorporating phase contributions from B0 and B1.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Weiger M, Pruessmann KP. MRI with Zero Echo Time. Harris RK, ed. eMagRes. 2012;1:311-322. doi:10.1002/9780470034590.emrstm1292.

2. Dixon WT. Simple proton spectroscopic imaging. Radiology. 1984;153(1):189-194. doi:10.1148/radiology.153.1.6089263.

3. Reeder SB, Pineda AR, Wen Z, et al. Iterative decomposition of water and fat with echo asymmetry and least-squares estimation (IDEAL): Application with fast spin-echo imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54(3):636-644. doi:10.1002/mrm.20624.

4. Levin YS, Mayer D, Yen YF, Hurd RE, Spielman DM. Optimization of fast spiral chemical shift imaging using least squares reconstruction: Application for hyperpolarized 13C metabolic imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58(2):245-252. doi:10.1002/mrm.21327.

5. Weiger M, Brunner DO, Tabbert M, Pavan M, Schmid T, Pruessmann KP. Exploring the bandwidth limits of ZTE imaging: Spatial response, out-of-band signals, and noise propagation. Magn Reson Med. 2014:1-12. doi:10.1002/mrm.25509.

6. Man LC, Pauly JM, Macovski A. Multifrequency interpolation for fast off-resonance correction. Magn Reson Med 1997;37:785-792.

7. Pruessmann KP, Weiger M, Bo P, Boesiger P. Advances in Sensitivity Encoding With Arbitrary k -Space Trajectories. 2001;651:638-651.

Figures